A friend recently informed me he wanted to kill himself.

His delivery was blunt, to the point; “I just feel like ending it all.” This shocked me on one level, and on another the news was not unexpected. He’s been going through a lot. I cautioned him that doing this was a bad idea, not the least of which was that he wouldn’t be able to enjoy beers on a sunny day with me and that frustrated me. It frustrated him, too. We’ve talked a lot since then and he has not attempted suicide.

Like many veterans, he’s experienced trauma, that which is generally associated with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. My friend Scott Huesing wrote in his bestselling book, Echo In Ramadi, that we should drop the ‘D’ in the acronym, as have my friends at 22zero.org, who counter that people experiencing PTS don’t have a disorder. They are damaged and need to heal. Calling them something other than that is detrimental. In the interest of unified support, I agree we should drop the ‘disorder.’

One need not be a combat veteran to exhibit the signs and symptoms of PTS. The affliction besets first-responders; medical service workers; and even those who might not associate their inner struggles with something like a bad car accident; being a victim of violent crime; losing a monetary fortune; working with a toxic boss; or even witnessing something traumatic in their youth which remains unresolved.

The point is that PTS can and does affect anyone and working through it is often difficult because one has to ask for help, even if they don’t know what is spiraling within them. It’s okay to say, “I’m not okay.”

Please consider becoming a paid subscriber. It’s $2 a week—less than a beer when you go out and perhaps as satisfying without the caloric deficit—and $80 annually. It really helps me as a writer, and you’ll receive access to exclusive content including advanced project previews and releases. Thanks!

Truth in lending, I coexist with my own PTS. Over a 24-year Marine Corps career, much of it served in violent areas characterized by combat operations, I was bound to pick up some heavy baggage. I try not to let it saddle me, but every once in a while my PTS bubbles up in the form of a bad image, shame in a memory, guilt at my decisions, or someone calling me out in the comments of a recent podcast appearance by stating, because I served in a support role (I’ve NEVER overstated my service), I’m not ‘elite enough’ to their liking. Fuck the haters, I say, but it still dredges up self-conscious berating, never mind wondering what my service was worth. At least I did it.

My friend Lori Butteries, herself a Navy combat veteran, wrote in her excellent article in The Havok Journal on delayed onset PTS[D]—my brackets—that some veterans put their experiences on pause. This doesn’t mean they go away, only that these lie dormant until they are addressed. Unfortunately, most people aren’t afforded the opportunity to decide when that will happen, so these moments often manifest in the form of ill-timed, emotional outbursts or confrontation. These episodes are cries for help.

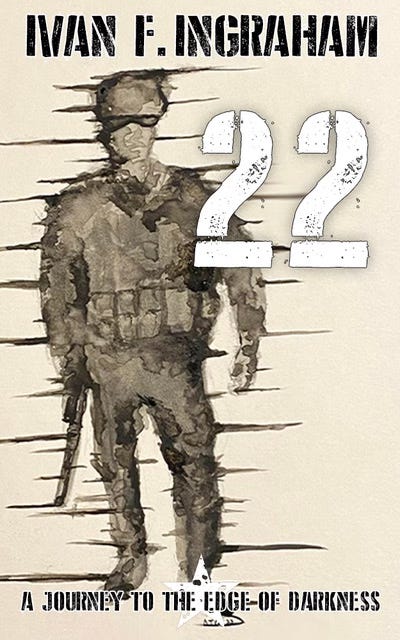

May is veterans mental health month and this is the theme of my articles over the next few weeks. There is a disconnect between veterans and the general populace and I want to raise awareness so people will have conversations, however hard, with friends who might feel they are running out of options. It is also why I wrote my book, 22: A Journey to the Edge of Darkness, in hopes that someone who is struggling will read it, reconsider their choice to decide on a selfish, short-term solution to a long-term problem, and stop to appreciate what they have.

In fact, another friend who read 22 informed me he nearly called me while reading it to check on me, such is the gravity of the subject matter. I assured him I was fine, not to worry, and that I appreciated his sentiment and concern. There are parts of the book that are autobiographical, but the attempt to take my own life isn’t one of them.

I encourage veterans and others suffering from PTS to reach out for help in any manner they feel comfortable. It could be an anonymous call to a prevention hotline (though the recent culling the VA suicide prevention hotlines by our government in the interest of saving a couple bucks doesn’t send a positive message—thank you for your service, indeed), reaching out to a friend, going to the church of your choice for the first time, or finding a support group.

For those with PTS, I get it. You’re not alone, though I know it can feel that way. We don’t need more medication and sedatives, we need to have conversations where people seek to understand without shame of judgment.

In the main, there are options, but one thing I know in this crazy, over-connected world in which we all attempt to exist is that nothing beats human interaction with the right people. It really helps, and this coming from a guy with strong misanthropic tendencies and a penchant for isolation.

If you know someone who is hurting, meaningfully reach out to them. You don’t need to be a trained psychologist to help. That call may offer hope. A kernel of hope is a wellspring for some. Look for that in the darkness and not at the darkness itself. Walk to the edge, if you need to explore what the other side looks like, but always return.

Hang in there, everyone.

Well said. I have this conversation with friends over coffee on a weekly basis. Honest and open dialogue with people who can be trusted to listen can be a very good step and help maintain positive changes. Thanks for the article!